What About WeChat? Another Front to Watch for PRC Manipulation Ahead of U.S. Elections

The Tencent-owned app deserves closer scrutiny to preserve free expression and access to information for Chinese American voters

With just under a week to go until the 2024 U.S. elections, there is one vector for potential PRC influence—or even interference—that has received relatively little attention: WeChat, a multipurpose mobile phone app owned by Chinese tech giant Tencent and used by millions of Chinese-speaking Americans.

It is hard to get a read on what is happening on the decentralized platform and frankly, I have not personally had the time to do a deep-dive investigation of current content ahead of the elections. Nevertheless, WeChat is an important and often overlooked space to watch with potentially significant impact, especially during such a close election.

Given the geographic distribution of Chinese-speaking Americans, there are probably not many WeChat users in swing states crucial to deciding the presidential elections, but there are a good number in several Congressional districts with tight races. Any manipulation there could have ramifications for both those contests and broader control of the House and Senate.

So for this latest post on PRC-disinformation and U.S. elections, I’ll run through what WeChat is, why it matters, past evidence of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) influence on the platform, what information is available ahead of the 2024 polls, and what to watch for in this last homestretch before election day.

Let’s dive in!

What is WeChat?

WeChat (known as Weixin in Chinese) is a mobile phone application that is ubiquitous in China, with functions that include private and group messaging, digital payment options, news feed subscriptions, and a variety of ‘mini-programs’ that function as apps within the app. It reportedly has over one billion active daily users, rendering it one of the most widely used apps in the world, though the vast majority of users are in one country: China. The app is owned by Chinese tech giant Tencent—a firm with close CCP ties and as of 2023, a small government stake in the company. Tencent is also known for its popular QQ instant messaging platform and video games.

From WeChat’s inception, the app has been forced to comply with strict CCP information controls within China. And indeed, there is evidence of close monitoring and censorship of WeChat users within the PRC, including the shuttering of thousands of independently operated news feeds (typically referred to as “self media”).

Surveillance and reprisals for WeChat posts have included numerous cases of prosecution and imprisonment of prominent human rights activists and lesser-known ordinary users who shared content criticizing local officials, commenting on disasters like floods or mocking Xi Jinping. An untold number of Uyghurs, Tibetans, Falun Gong practitioners, and other members of persecuted religious and ethnic communities have also been imprisoned for sharing information on the app or using it to communicate with family and friends outside China.

WeChat censorship and surveillance outside China

Although WeChat’s primary user base is in China, an estimated 75 to 100 million people outside the country use the app. Among them are millions of members of the Chinese diaspora in countries like Canada, Australia, Malaysia and the United States. As more Chinese-speaking users—especially first-generation immigrants—turn to mobile apps for news consumption, WeChat’s influence as an information gatekeeper has increased.

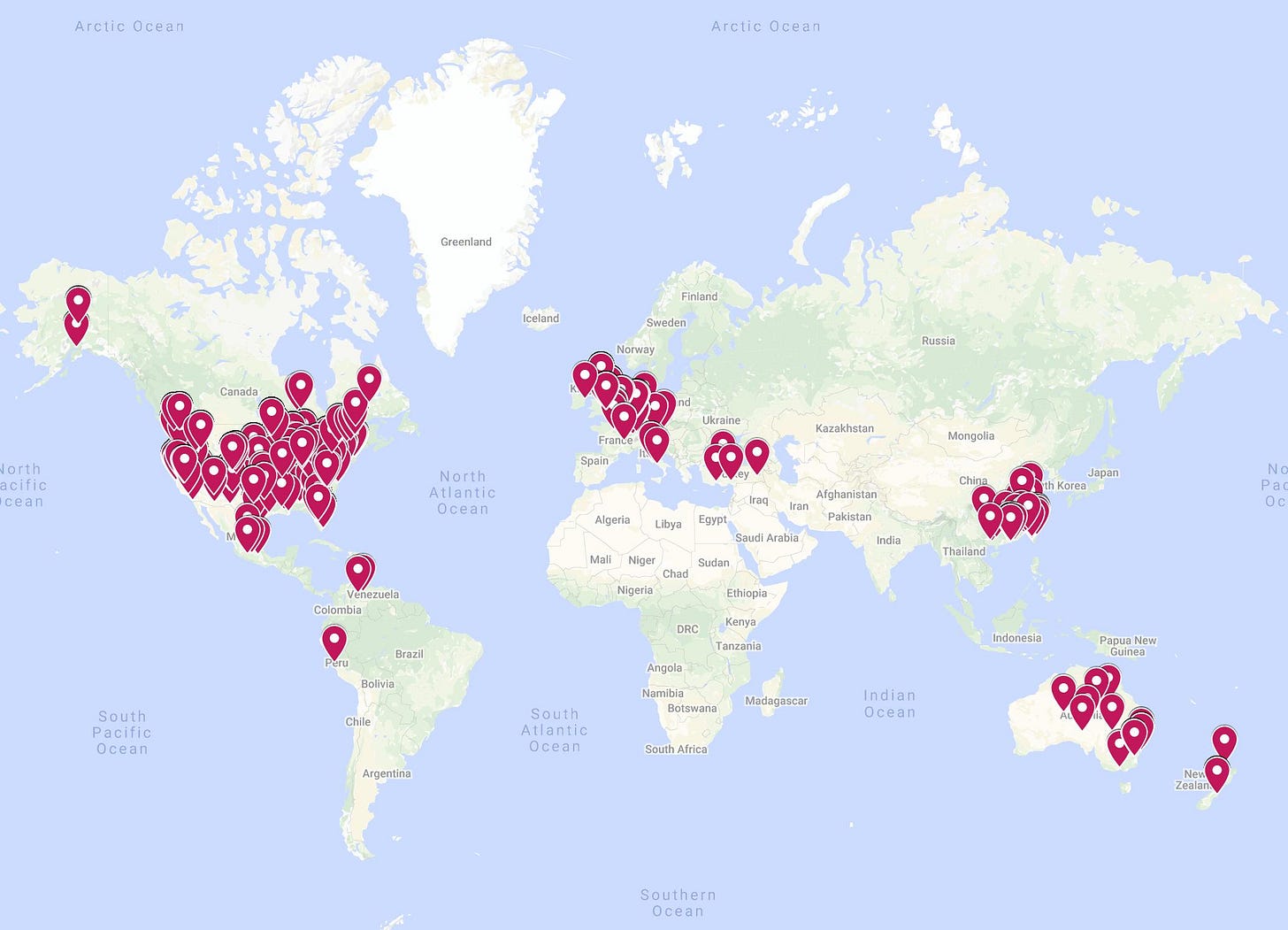

Evidence that politicized censorship and surveillance affects Tencent users outside China has also emerged over the past decade. A 2016 study by Citizen Lab found that once an account is registered with a Chinese phone number, it remains subject to mainland controls even outside the country. A 2020 study by Citizen Lab found evidence of systematic screening of messages by WeChat users globally for politically sensitive keywords, even if the messages were not subject to deletions. In 2019, Dutch hacker Victor Gevers found a repository of data indicating that WeChat was using keywords to intercept and capture “for review” millions of messages by users in at least 15 countries.

In recent years, there have been numerous anecdotal reports of WeChat users outside China facing deleted posts, shuttered accounts, or “shadow bans” (when a post appears published to the writer but is invisible to some or all other users) for posting information disfavored by the CCP. Such content moderation contributes to self-censorship, with news outlets or journalists that have WeChat accounts being careful what they post, lest they be shut down and years of building an audience on the platform gone to waste.

On a structural level, WeChat’s policies for account creation limit which foreign and diaspora media organizations, civil society groups, and journalists can share news on the platform. Its “official” or “public account” feature allows users to broadcast articles to a large audience (as opposed to circulating content in closed groups of contents). But this is only available beyond four posts per month to entities registered in China or for those with a Chinese national willing to provide an ID number (a risky prospect if an account aims to share news and views critical of the CCP). This structural curb preemptively bars news organizations, civil society groups, or journalists based outside of China and which are focused on human rights or other content critical of the Chinese government from even creating such accounts.

WeChat use and politicized restrictions in the United States

The impact that WeChat’s policies have on free expression is also clearly evident in the United States, home to over 4 million Chinese Americans per the 2020 Census (and at least another 1 million Americans who identify as Chinese alongside another ethnicity). WeChat is heavily used among Chinese-speaking Americans and others who maintain personal or professional contacts with people in China. It is difficult to nail down a precise count of WeChat users in the United States, but estimates cite 19 to 22 million overall users and approximately 2 to 3 million monthly active users.

In recent years, numerous reports have emerged of WeChat users in the United States encountering politically motivated censorship on the app after expressing or sharing content critical of the CCP, Xi Jinping, or the Chinese government.

In a 2023 article for Foreign Policy, scholar Seth Kaplan cites several examples of Chinese American users—like Lydia Liu—who faced censorship. Liu had built up an audience of 250,000 followers for her updates on daily life in the United States, until WeChat censors apparently decided it was too positive a perspective on American life to pass muster with CCP propaganda directives and suspended her account. This is just one example of how, as censorship expands within China and an ever-growing list of topics and keywords are deemed “sensitive,” such restrictions also seep across to WeChat users in the United States.

For readers who would like to gain a deeper understanding of the impact this has on Chinese speakers in the United States, a January 2020 lawsuit filed against Tencent in California is a must read. It was filed by the prodemocracy group Citizen Power Initiatives for China (CPIFC) on behalf of the rights group, its founder (prominent activist Yang Jianli) and six plaintiffs.

The complaint documents different forms of censorship, reprisals by Chinese security agents against plaintiffs’ family in China, and the consequences for users’ free speech, privacy, mental health, and livelihoods. According to the complaint, “CPIFC’s ongoing investigation has uncovered hundreds of examples of…harms, all flowing from WeChat users in the United States… making comments perceived as critical of the Party-state.” U.S.-based users interviewed by the organization when preparing the filing reportedly describe:

living in fear that they or their loved ones will be punished for their postings critical of the party-state, and … having to suppress the human urge to voice their thoughts and feelings to their social networks out of such fear—that is, to engage in extreme self-censorship.

WeChat’s impact on diaspora journalists and media in the United States was also evident from a Freedom House survey of US-based Chinese language reporters and commentators I helped conduct when working there. As I wrote in the U.S. case study on Beijing’s global media influence published by the organization last year, the research team found that:

Respondents from a range of outlets (including US-funded broadcasters, individual commentators, and privately owned Chinese media or news aggregators) reported that either they personally or their news outlet had experienced politically motivated censorship or shadow bans, had a WeChat account shuttered, or was unable to open an account. Similar constraints apply to civil society and human rights groups….

[Such] exclusion of more independent news outlets and critical voices from WeChat… skews the diversity of perspectives and information sources available to Chinese-speakers in the United States.

It was partly for these reasons that the Trump administration in 2020 included WeChat in a prospective ban issued by executive order. The attempt was blocked by a federal judge for violating the First Amendment and President Biden formally revoked it, replacing it with a national security review. But even as other apps owned by China-based companies have stayed in the spotlight—notably TikTok—the risks posed by WeChat appear to have all but been forgotten.

Past examples of election-related interference or misinformation

And yet, the risks are real and have been at least partially documented. A November 2021 investigation by the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab found evidence that China-linked WeChat accounts had spread disinformation ahead of elections in Canada, specifically amplifying narratives critical of the Conservative Party and its candidates. Subsequent Canadian government inquiries have similarly voiced concerns of seemingly coordinated campaigns on WeChat spreading falsehoods about Chinese Canadian MPs and election candidates like Kenny Chiu, with some suspecting these could have cost him the election.

In the U.S. context, scholar Seth Kaplan mentioned above argued in a June 2023 piece for the National Interest that voting patterns among Chinese Americans in recent elections appeared to track amplification or suppression of certain accounts and narratives on WeChat, first favoring Donald Trump in 2016 (with some pro-Hillary Clinton material demoted and websites like the Asian American Democratic Club for Hillary banned from the platform). Partway through the Trump administration, Kaplan argues that WeChat public and influential personal accounts—including some belonging to Chinese state-owned outlets like Global Times—“changed from pro-Trump to pro-Biden,” while the platform enabled Democratic groups in 2020 to use the app in ways they had been unable to in 2016; all the while, pro-Trump voices were “bullied” and “ostracized.”

Again Kaplan cites correlations evident in Chinese-American presidential voting patterns, which favored Biden more strongly compared to other Asian Americans. Other factors were likely also at play, but the shifts are nevertheless disconcerting in terms of the platform’s flip-flopping moderation and its potential influence on voters. Additional academic and civic group studies have pointed to the wide circulation of misinformation on WeChat regarding topics like the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 polls, and 2022 midterm elections.

What to watch for in the 2024 elections

In the run-up to the 2024 elections, I was able to find only one piece of research that seriously examined what is happening on WeChat and even that analysis offers only partial insights. In August, the CAA, a California-based progressive group representing the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, published a report examining misinformation in Chinese-language content consumed by Chinese Americans. Central to the effort was the capture and analysis by its fact-checking project PiYaoBa of 228 of posts on WeChat, X, and YouTube, regarding the 2024 elections that were assessed to contain disinformation.

Overall, the report found that a larger proportion of these posts tended to support Donald Trump and Republican policies, while attacking President Biden and Democratic ones. Some also included AI-generated content. Perhaps one of the study’s most notable findings was actually that more content identified as disinformation was found on X compared to WeChat. WeChat posts still comprised 25% but this was a steep drop from 54% ahead of the midterms.

Unfortunately, the report does not include more in-depth analysis specific to WeChat about which narratives are being promoted, whether any of those accounts are visibly or presumably linked to the CCP or its proxies, or if any disinformation posts were found targeting Congressional candidates. It does state that the group’s own fact-checking posts have encountered censorship on WeChat. Moreover, the authors indicate that users are taking notice of WeChat’s manipulations such that “many Chinese-language social media influencers are transitioning out of WeChat because of censorship” and are migrating to X.

WeChat remains a real vulnerability in the U.S. information landscape, with potential areas of concern for both major political parties.

Down-ballot races where WeChat could matter

This limited research did not shed light on any WeChat manipulation targeting Congressional candidates, but an analysis of available data on Chinese voter demographics and close congressional races yields several where a WeChat-based influence or smear campaign—should it occur—could have an impact.

According to the research group AAPI Data, there are over 2.4 million Chinese American adults eligible to vote this election. Notably, almost 2 million of these voters—over 80 percent—are located in just five states, according to organization’s analysis.

Looking at this data, among Senate races, the one in Texas between Ted Cruz and Colin Aldred, stands out as being potentially vulnerable and a possible target for the CCP—if it were to try to use WeChat to influence voter views of candidates—especially given that Cruz was sanctioned by the Chinese government in 2020 (see my post here for more on factors rendering candidates potential targets). Let’s hope the Cruz campaign or relevant U.S. agencies are monitoring WeChat chatter there.

On the House side, the Cook Political Report identifies as a “toss up” several races in California and New York, the two states with the largest population of Chinese American voters. All are Republican incumbents defending seats in Democratic majority states. The candidates in California are John Duarte (CA-13), David Valado (CA-22), Mike Garcia (CA-27), Ken Calvert (CA-41), and Michelle Steel (CA-45).

Steel checks one of the boxes I flagged in my August post as potential triggers of greater CCP ire—being a member of the Congressional-Executive Committee on China, which holds hearings on human rights violations in China. Her being an Asian American critical of the CCP also likely irks the regime (several of the MPs targeted with disinformation campaigns in Canada were Asian Canadians). In New York, two races to watch are the seats that Anthony D’Esposito (NY-4) and Mark Molinaro (NY-19) are defending.

The latest survey data on Chinese American voters indicates that a larger proportion are registered Democrats (56%) compared to Republicans (21%) or independents. So, losses for Republicans in districts with a high proportion of Chinese American voters needn’t indicate a WeChat-amplified influence campaign per se.

Nevertheless, it would be wise of the relevant campaigns and election officials in these areas to work with civil society groups and independent researchers to monitor any suspicious activity or falsehoods about candidates from both parties that may be circulating widely on WeChat, especially by accounts or individuals with known CCP or Chinese government ties.

Closing thoughts

The above analysis may offer more questions than answers. Hopefully, there are journalists and researchers reading this who can take up the cause of answering these questions with further investigations. What is certain is that WeChat remains a real vulnerability in the U.S. information landscape, with potential areas of concern for both major political parties.

An outright ban of the app is far from an ideal solution from both a practical and Constitutional perspective. Even so, greater policymaker scrutiny of the platform is urgently needed. That should include demands for more transparency and accountability from Tencent executives and opportunities for Chinese Americans and news outlets who have been silenced on WeChat to have their voices heard.

Such actions are worth taking long after the upcoming elections. They would help ensure that members of the Chinese diaspora—including those critical of the CCP—are able to partake in public life and enrich our political debate like any other American.

Thank you for covering this topic, Sarah. Its important and yet receives little attention. I would go further and say that any US effort to counter Chinese disinfo campaigns worldwide must incorporate a strategy for WeChat given the tens of millions of users outside China. More broadly, the Chinese language diaspora media ecosystem is one of the few ways we can undermine CCP narratives within China. What Chinese diaspora, students, and tourists read outside the country seeps back into it. While we struggle to penetrate the Great Firewall, we can work through the overseas media ecosystem to reach people inside the country.

Hi Sarah, I really like this article you wrote. I am a student at The University of Dayton and I wanted to reach out regarding a paper I have to write. I am writing an essay for my international mass media class, researching the role of the CCP/Chinese state media in shaping national identity and global perceptions, with a particular focus on its influence within the Chinese American community in San Francisco. Given your expertise in Chinese media, I would be incredibly grateful if you would be willing to participate in an interview for my research. I believe your insights would be invaluable in helping me understand the complex relationship between media narratives, identity formation, and the broader geopolitical implications of media control. let me know if you would ever be interested my email is @Andersonl20@udayton.edu.